The transparency conundrum

True transparency requires more than making information available.

According to Rio Tinto, it was a ‘misunderstanding’ with the local Indigenous community that resulted in the destruction of 46,000 year-old sacred sites in May this year. The company had Government approval and stakeholders had been informed. All boxes checked. Obviously, that was not enough.

Since 2015, the Australian Government has been a member of the Open Government Partnership (OGP), committing to support the goals of increasing the transparency and accountability of government. The first OGP Global Report (May 2019, page 20), identifies these as generally lacking in health procurement decision-making in the 78 nations involved. In this article, I assume procurement includes the registration and reimbursement of therapeutic interventions by the Government on behalf of Australian taxpayers. My thesis being that openness may not necessarily be transparent, using two examples to illustrate.

Example 1. The presentation of options by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for which type of medicines would have evaluation status made public.

Option 1: maintain TGA’s current publication arrangements [to not make public]

Option 2: list all applications accepted for evaluation

Option 3: list all applications at two different time points

Option 4: list applications of innovator medicines of highest public interest, but not generic or biosimilar medicines

The explanations given for providing Options 3 and 4 include: ‘Generally, there is less public interest in whether a generic or biosimilar medicine is under evaluation by TGA in Australia’, and ‘Earlier publication of generic or biosimilar approvals prior to ARTG entry allows more transparency of forthcoming competition to sponsors of originator medicines and potentially, purchasers of biosimilar and generic products.’

The TGA has been in the unenviable situation of neither being able to confirm nor deny whether a particular medicine is currently in the evaluation process. Other similar jurisdictions, such as Europe and Canada publish this information. It is a good initiative. The particular drivers of this 2019 consultation on transparency were: from the TGA side, inconsistencies with other agencies, especially evident during joint evaluations of new molecules; from the innovator sponsor side, more time to initiate legal proceedings against potential patent infringing generics/biosimilars and avoidance of liability for damages by the Commonwealth; and from generic/biosimilar applicants, maintain the status quo.

The inclusion of Options 3 and 4 show that there is an awareness of the potential negative commercial/financial implications to applicants and the Government of originator sponsors knowing the timing of registration of a generic or biosimilar. Is this made clear? Does ‘less public interest’ justify being selectively transparent?

Example 2. Measures associated with the ongoing Medicines Australia-Commonwealth Strategic Agreement PBS process improvements include the PBAC preference for greater transparency to be introduced in Public Summary Documents (PSDs) through a standardised approach to redactions.

Objectives of proposed PSD Changes – PBAC (Medicines Australia, Feb 2020)

•Increase transparency of PBAC’s decision-making processes.

•Publish PSDs in an efficient and consistent manner through establishment of a standardised approach to redacting information.

•Provide consumers with access to information to assist with making decisions about their individual health needs.

•Increase the public’s understanding about PBAC decisions.

•Align Australia’s practices with leading international jurisdiction approaches*.

*This refers specifically to the additional, and unexpected, push for PSD inclusion of all clinical data provided in PBAC submissions, irrespective of the publication status nor commercial impact. While no other jurisdiction currently requires it, other countries are considering in response to calls for increased pricing transparency (WHO, WHA, 2019).

While appropriate that the PBAC want to clearly indicate how each recommendation was reached, what is the point of providing even more information in PSDs when the existing format is, realistically, inaccessible to anyone without disease and technical knowledge and an appreciation of the meaning of uncertainty in this context? Inclusion of a summary in lay-man’s language in PSDs would go much further towards openness. It is like providing a patient with a copy of his/her CT scan and the report without an explanation as to what it means.

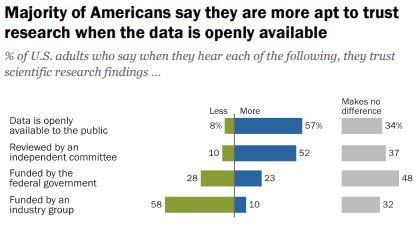

“Trust and Mistrust in Americans’ Views of Scientific Experts, Page 24

Do we want people to be able to understand the information OR is the fact that it is openly available more important?

According to a 2019 Pew Research survey, it is the later. Americans confidence in scientific findings are most influenced by open public access to data and independent committee reviews. There appears to be no similar survey providing Australian opinions.

Scientific journals are strongly encouraging authors to make datasets open source at the time of study publication with the intent of it becoming a mandatory requirement. Should sponsors of reimbursement submissions expect anything different? It is notable that journals target technical audiences, while PSDs are ostensibly for consumers (patients, healthcare professionals, competitors).

Before public release of information, consideration should be given as to who will use it, for what purpose(s), and the most appropriate release format, which is what the TGA and PBAC have undertaken via consultation in the examples provided. Is it enough?

Note: There is an opportunity to voice your opinion on ‘What does open government mean to you’ as input to the Third National OGP Australian Action Plan 2020-2022.

Image source: Jim Pavlidis