Death, be not proud

The release of Australian mortality data by the AIHW brings to mind Donne’s sonnet, although causes of death are no longer the ‘kings and desperate men‘ attributed in c.1610.

In 2017, there were 160,909 deaths registered in Australia, 66% among people aged 75 or over (60% males and 73% females). The median age at death was 78 years for males and 85 years for females.

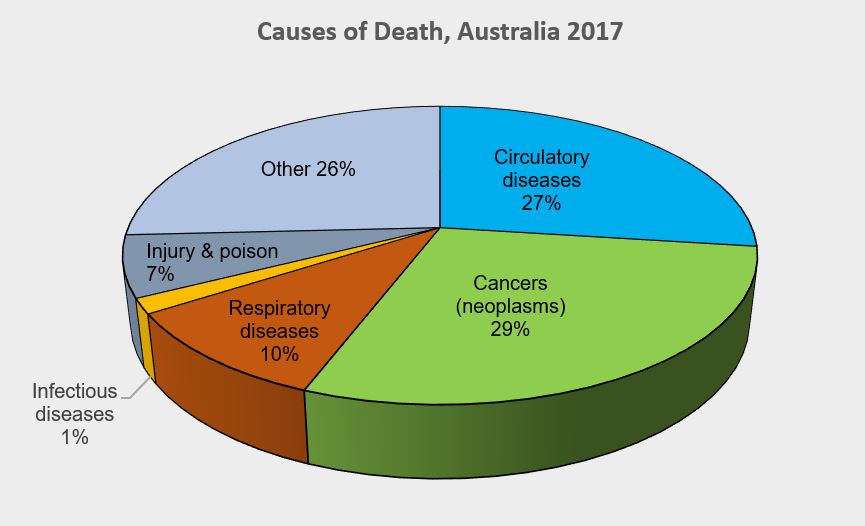

Overall, cancer (neoplasms) was the leading cause of death. At 29%, clearly easing circulatory diseases (27%) out of the top spot for the first time. The leading cause of death for males was coronary heart disease (13%). Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the leading cause of death for females (11%), followed by coronary heart disease (10%). Cerebrovascular disease (which includes stroke), lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) made up the top 5 leading underlying causes of death in Australia in 2017 for both males and females of all ages combined.

In 2017, the difference in death rates between the sexes was the narrowest ever recorded. The greater than 70 % reduction from a high in 1968, is considered to be due to a drop in deaths from circulatory diseases. Factors at play include improvements in medical care (surgery, diagnosis and pharmaceuticals), and lifestyle changes (smoking, diet and high blood pressure).

Child (aged 0-4 yrs) mortality accounted for < 1 % of all deaths in the period. A major improvement on the 26 % reported for 1907, however still too high for the families involved. Work continues on access to and quality of neonatal health care; community awareness of risk factors; and increasing coverage of universal immunisation programs.

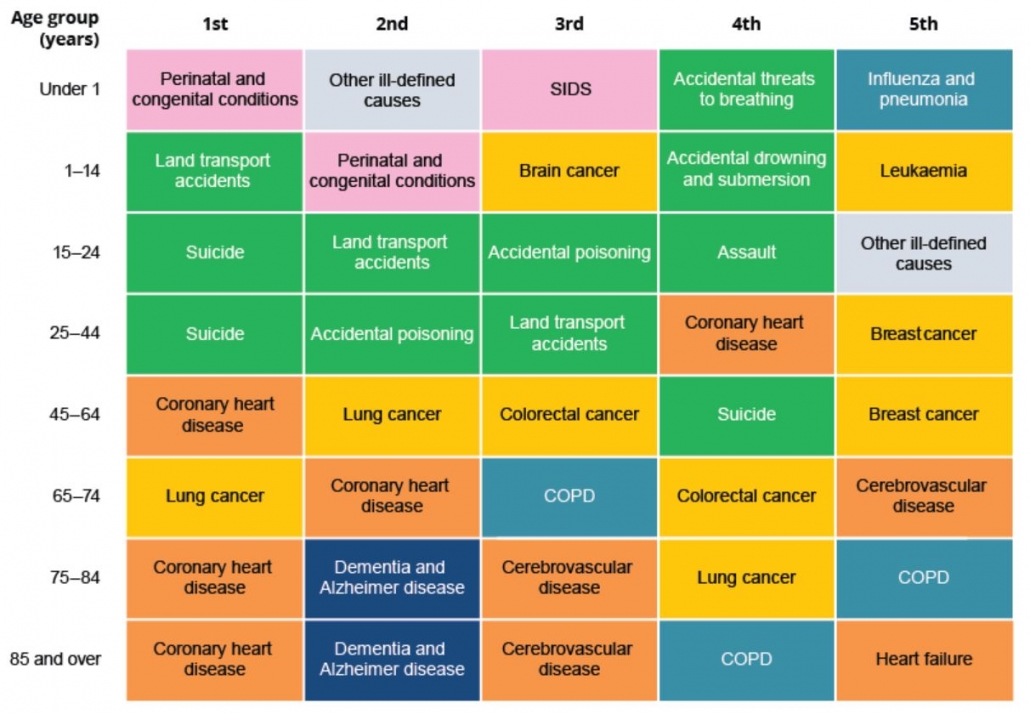

As well as differences by gender, the leading causes of death also vary by age (refer graphic):

- Among infants, perinatal and congenital conditions accounted for 79 % of deaths;

- Land transport accidents were the most common cause (11 %) among children aged 1–14 .

- Suicide was the leading cause of death among people aged 15–24 (35%), followed by land transport accidents (22%);

- For people aged 25–44, it was also suicide (21%), followed by accidental poisoning (12%);

- Chronic diseases feature more prominently among people aged 45 and over. Coronary heart disease was the leading cause of death for people aged 45–64, followed by lung cancer;

- For people aged 65–74, it was lung cancer followed by coronary heart disease;

- Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the second leading cause of death among people aged 75 and older, behind coronary heart disease.