Healthcare Buyer Beware

First screened at the Tribeca Film Festival in April 2018, and still available on Netflix, The Bleeding Edge is a documentary that could have easily been made about any sector of the health care industry.

No medical intervention is without risk, and although informed consent includes a discussion of potential negative outcomes, health consumers are invariably in no position to make an informed decision.

Firstly, they do not have the requisite medical knowledge, and no amount of internet searching can substitute for formal education and clinical experience in a field. Secondly, objectivity must be affected when a health issue is impacting an individual’s quality of life to the extent that he/she is considering something invasive, be it a medicine or procedure.

Consumers are encouraged to ask questions, and seek a second opinion. However, when you may have already waited months for an appointment, and then paid a substantial out of pocket for the consultation, it takes courage, as well as time and money, to seek the opinion of another medical specialist. This is a very real situation for patients, as confirmed by the Australian Government Department of Health’s newly launched Medical Costs Finder website, and as reported in the media last week.

For those who have missed seeing the documentary, it explores Bayer’s permanent birth control device Essure, Johnson & Johnson’s transvaginal mesh, the Da Vinci Surgical System, and chrome-cobalt hip-replacements. Patients who have experienced adverse effects are followed as they try to regain their health; search for answers; support others; and make efforts to raise the alarm. Unlike scientific data, the film personalises and, despite the MedTech industry viewpoint, it clearly shows what ill health, irrespective of the cause, can do to a person’s life.

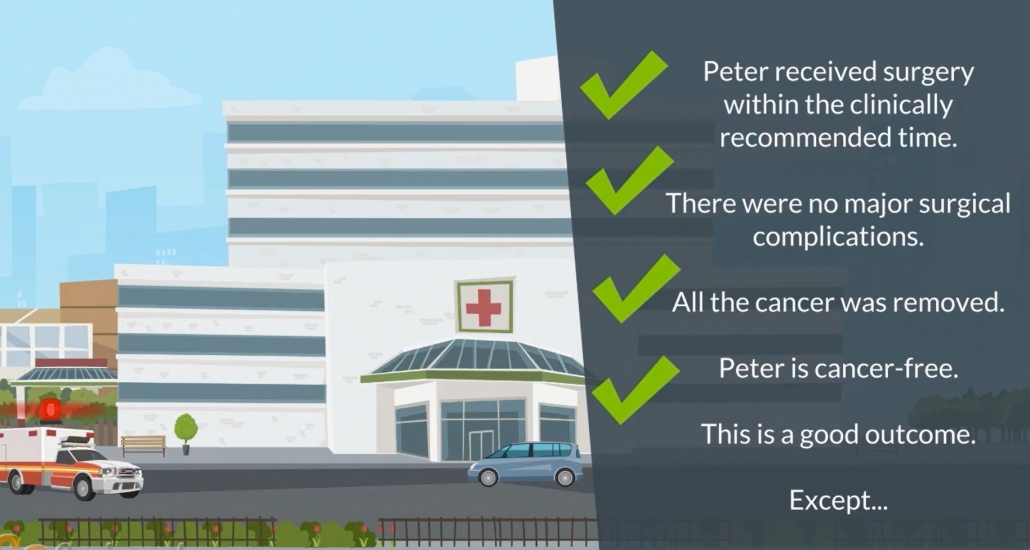

The documentary also highlights how an intervention can be experienced very differently depending on your perspective. This issue is illustrated using PSA levels as the basis for prostate surgery in a 2018 video on value-based healthcare produced by the Metro North Hospital and Health Service in Queensland. Over diagnosis of prostate cancer and over servicing with prostatectomy are well documented. Urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction are frequent side effects that are debilitating for patients, while from the health sector viewpoint, the treatment has been a success (see screen shots from the video).

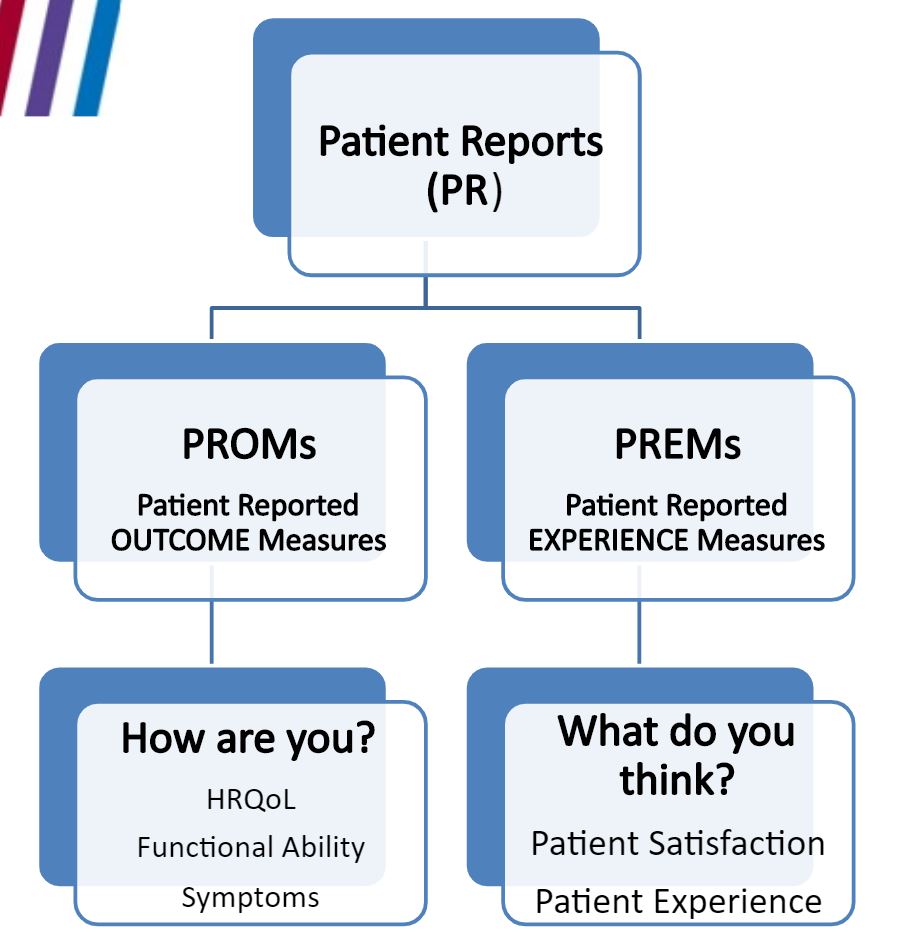

This disconnect is behind increasing calls to integrate patient feedback into clinical practice by use of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) (see figure).

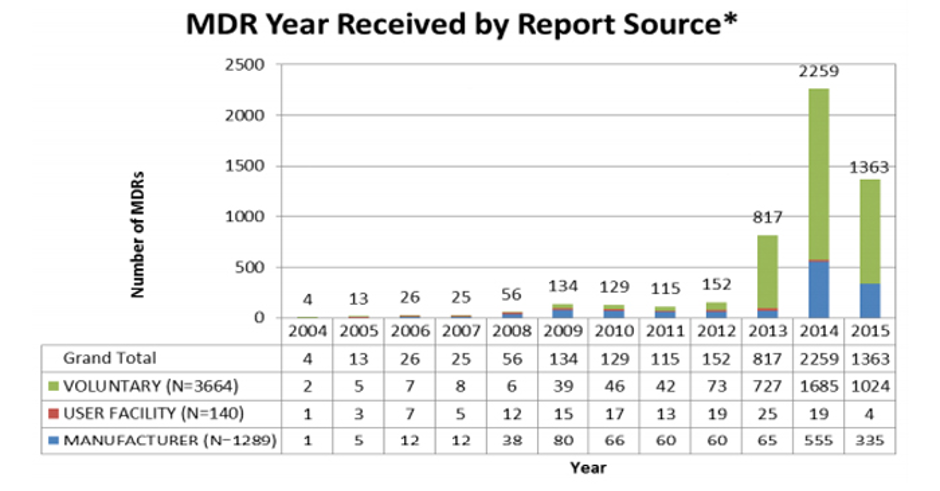

A concern focused on in the documentary is the lack of evidence required for medical devices to be approved for marketing in the US. The FDA’s 510(k) pathway enables medical devices to be approved if the manufacturer demonstrates equivalence to a device already on the market. This is considered less rigorous than the standards that apply to new medicines.

Parvizi and Woods (Clinical Medicine 2014;14(1):6-12 ) compare and contrast regulations for medicines and devices and explain that differences are a function of the nature of the challenges in defining and monitoring the safety and performance of devices under conditions of use. Namely, the large number of types of medical device in use; short timelines of innovation with a medical device typically changed by incremental steps every 1–2 years; and the main causes of adverse incidents being sporadic manufacturing faults, long-term wear (particularly in the case of implants) and operator factors.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is responsible for medical device approvals in Australia. Compliance with a set of Essential Principles (EP) for the quality, safety and performance of a medical device is required to be demonstrated by manufacturers to achieve marketing approval (ARTG listing). The rigorousness of requirements depends on classification of risk level for different classes of device. For example, for surgical retractors classified as low risk (Class I), a sponsor can self-certify that their product meets the EPs. Active implantable medical devices (AIMD), such as pacemakers and those include medicines, tissues or cells, are the highest risk and must be assessed in full by the TGA.

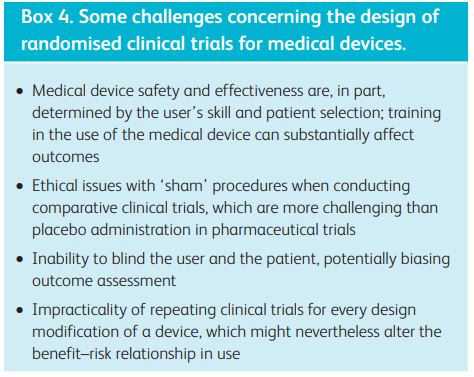

EP#14 Clinical evidence states:“Every medical device requires clinical evidence, appropriate for the use and classification of the device, demonstrating that the device complies with the applicable provisions of the Essential Principles.” It is acknowledged that in some circumstances clinical investigation data are not available or are insufficient in quantity or quality (see Box 4 from Parvizi and Woods 2014). In this situation clinical investigation data from a ‘substantially equivalent’ device such as a predicate or similar marketed device may be used to support the safety and performance of the device under assessment.

In response to public concerns, the TGA published an overview of regulation of Medical Devices in late 2018. It includes that “The TGA has only recently started accepting US FDA 510k approvals to support applications for some implantable medical devices, and these applications are being subjected to further scrutiny by us to ensure that devices that use this pathway are meeting Australia’s requirements.”

Risk benefit evaluations are an ongoing conundrum for health consumers. Until the equation can be communicated with clarity, the same warning must apply as with any other purchase, caveat emptor.

Note: A week prior to the film release in 2018, Bayer removed the Essure birth control device from the U.S. market. The Essure contraceptive device was cancelled from the ARTG on 9 February 2018. Since the device began supply in Australia in 1999 until 6 August 2018 the TGA received 59 adverse event reports relating to women implanted with the Essure device. The reports included changes in menstrual bleeding, unintended pregnancy, chronic pain, perforation, migration of the device, and allergy/hypersensitivity or immune-type reactions. Surgery, including hysterectomy, was required in some instances to remove the device.