The PBS goes to Canada

Taxpayer funded national programs providing universal access to prescription drugs are longstanding policy in Australia, NZ and UK.

Considering the establishment of a similar program in Canada, where largely private province-based schemes* currently operate, presents an opportunity to consider what is lost when these programs are the sole focus of pharmaceutical policy.

Advocates of such schemes point to cost-effective product selection and savings generated by lower and reducing generic and brand name prices. The principles of universality, equity of access, safe & appropriate prescribing, and value for money are paramount.

The Minister of Health, the Hon Greg Hunt MP, regularly commends the foundation role that the PBS plays in the Australian health system. While such programs have reduced both overall expenditures and the average price paid per drug, like all policies, they often have unforeseen repercussions.

In her recent essay, Kristina Acri examined the potential unintended consequences of a publicly-funded national Pharmacare program in Canada. She reviewed the experience of New Zealand, Australia and United Kingdom to identify those aspects where reality has not matched the promise:

- Drug supply is put at risk by sole tendering & reference-based pricing policies, as well as use of cost-effectiveness analysis. For off-patent medicines, seeking the lowest price within a guaranteed supply framework should protect against shortages. However, whether appropriate or not, global factors and profit seeking influence where available drug supplies are sent. Dealing with drug shortages are an increasing occurrence for pharmacists, clinicians and patients;

- The scheme may not be universal. In Australia, 50 % of total drug expenditure is directly borne by patients, one of the highest cost-sharing rates in OECD countries after the far Northern European countries (ranging from Sweden 48 % to Iceland 58%) (OECD, 2015). Before introducing the scheme, how medications will be selected and what the costs will be to patients and taxpayers must be fully understood; and

- The likely impacts on access, health outcomes, costs, and innovation for patients, physicians, the market and the economy should be examined.

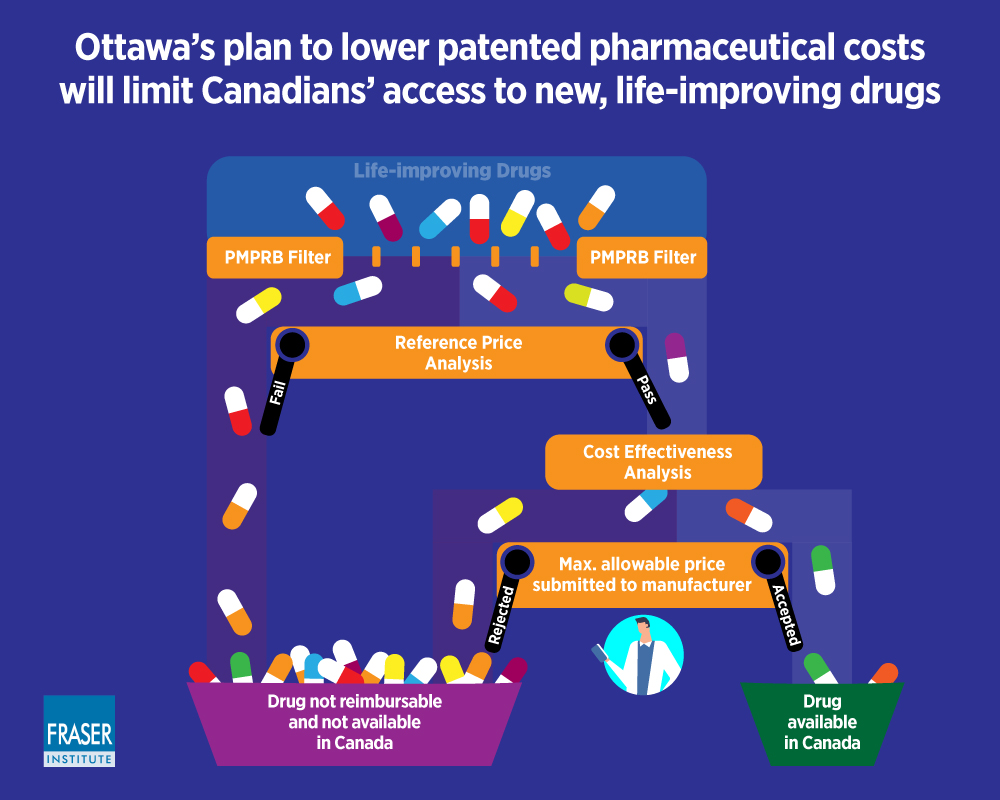

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is an independent quasi-judicial Federal agency established in 1987 under the Patent Act. The PMPRB ensures prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive.

In a similar review, Crosby et al. (2016) discuss that to control spending on universal schemes, access to new drugs is rationed, downward pressure is imposed on prices, and costs are pushed to individuals. They conclude that introducing a universal scheme to Canada would increase public spending, reduce patient choice to only subsidised medicines, delay access to new drugs and lead to inequities in coverage compared to the existing situation.

Globerman and Barua (2019) discuss the impact of the Health Canada proposed amendments to the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) procedures which will include the evaluation of the cost effectiveness of drugs by CADTH, into the determination of maximum allowable prices for patented drugs. They note that that these changes ‘seem to be focusing more on controlling expenditures on pharmaceuticals than on ensuring that Canadians have access to new therapies’. They advocate for an efficient level of expenditures on pharmaceutical drugs, not simply containing expenditures on those drugs.

‘In principle, cost-efficiency analysis is a technique for comparing the social benefits of a drug relative to its cost.

In practice, the conventional application of the technique arguably leads to an underestimation of the social benefits of new drugs.’

Despite these concerns, last month legislation introduced by Health Canada was passed and paves the way towards a PBS Canadian-style! ‘Government of Canada Announces Changes to Lower Drug Prices and Lay the Foundation for National Pharmacare.’ News Release, August 2019.

*A third of Canadians are covered by public drug plans which vary from province to province. Most are covered through their workplace by private insurance plans. Another 10% of Canadians have no coverage at all (Canadian Health Coalition, 2017).

References: (1) Kristina M. L. Acri (née Lybecker) The Unintended Consequences of National Pharmacare Programs. The Experiences of Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. The Fraser Institute, December 2018. Vancouver BC, Canada. (2) Steven Globerman and Bacchus Barua. Pharmaceutical Regulation, Innovation, and Access to New Drugs. An International Perspective. The Fraser Institute, January 2019. Vancouver BC, Canada. (3) Crosby L, Lefebvre C, Kovacs-Litman A. Is pharmacare the prescription Canada needs?. UWOMJ Drugs 2016;85(1):23-5.