Health Care Systems 2.0

Add periodic pandemics to the ageing populations, accelerating rates of chronic disease, innovative technologies and price increases that are already challenging the durability of healthcare systems and the phrase, ‘a perfect storm’ comes to mind.

Prioritisation

Prior to this recent challenge*, many countries have managed their health care system budgets by using a variety of prioritisation methods:

- In the case of newer therapies, health technology assessment (HTA) conducted in an environment of accountability and transparency, uses technical judgements of clinical and cost effectiveness to determine the most appropriate use of taxpayers’ money.

- For existing services, a value-based approach, i.e. stop using resources on items that contribute little patient outcomes, has become popular. Unfortunately, even if conducted systematically this is not so straight-forward. As noted by Professor Vlado Perkovic during a 2014 panel discussion, a survey carried out by the ANZ Intensive Care Society found only 5% of treatments given to an intensive care patient were supported by reasonable evidence. Similarly, in primary care, Mark Ebell and colleagues (2017) identified that just 18% of clinical recommendations in the literature were based on consistent, high-quality patient-orientated evidence.

- A similar focus on system and process inefficiencies and waste have been successful. For example, the UK ‘Sustainable Development Unit’ measured an 11% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions attributable to the NHS between 2007 and 2015 (in line with targets) while the level of health care activity rose by 18%. By 2017, the financial savings associated with this environmental sustainability (mainly energy, waste and water) rose to £90 (AU$182) million annually (Pencheon 2018). There are no shortage of ideas on ways to tackle inefficiencies and waste (see Bennett 2013), however in healthcare systems under strain, who has the time?

- In an effort to tackle ‘the crisis of medical excess’, Cochrane Collaboration launched a new field, Cochrane Sustainable Health last year. The aim is to engage its global network to focus on highlighting the overuse of medical diagnostics and treatments which harm people and also consume scarce resources leading to underdiagnosis and underuse in other areas.

Prioritisation decisions will face legal, political, commercial and ethical challenges

The pressure on budgets will escalate prioritisation decisions and as the impact is felt by more people, there will be public concern. Governments must proactively engage patients and the general public in the process. To date, those directly affected by access decisions become involved. This base of public participation needs to broaden to ensure continuing societal agreement with how decisions on spending finite resources are made. Understanding this, Littlejohn and colleagues (2019) have developed an online decision-making audit tool as a way to interact with stakeholders and help generate acceptance for the need for health prioritisation and the resulting decisions.

As parodied in the episode of ‘Yes Minister’, The empty hospital (BBC 2007), a hospital with no patients is extremely efficient to run. However, placing a greater focus on preventative health is a better way to reduce demand on health care systems. This could include initiatives to provide education to improve population health literacy combined with Government services focused on the social and environmental determinants of health and incentives for individuals to make responsible health choices .

Health care is big business. There are many vested interests who will lobby hard to maintain or improve their position. Incentives will also be needed to encourage identifying opportunities to improve efficiency and eliminate waste, a priority for those currently in the system. The poor take-up of Health Care Homes is an example of how a good idea can be derailed.

Crunch time?

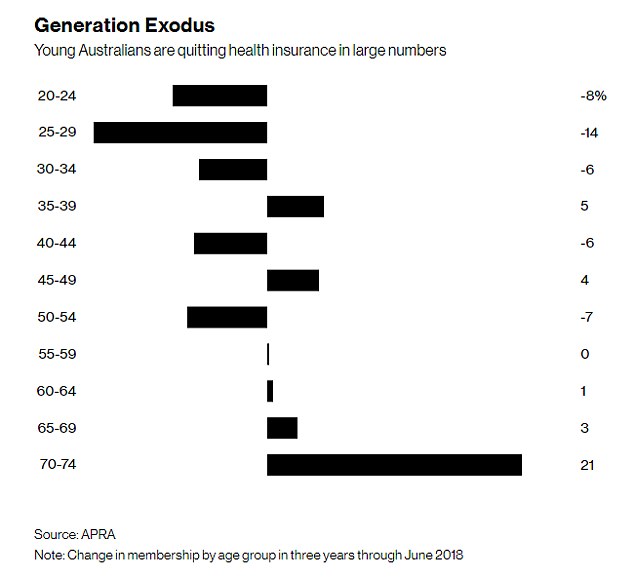

At that same breakfast, Professor Andrew Wilson ‘said the crunch point that would finally prompt action on health care reform would come when it was recognised that Australia’s states, which have very limited revenue raising capacity, could no longer afford to run hospitals. He was also concerned he said, about the affordability of healthcare for consumers, with rising out-of-pocket expenses, and a two-tiered health system that saw insured consumers able to access more extensive health care through the private system than those who used the public health system, even though 60+% of private health care costs were funded directly or indirectly by the public purse.’

Notes & References

*A prophetic report published last January by the World Economic Forum and Harvard Global Health Institute calculated that the annualised costs of flu pandemics alone are similar to those predicted to be caused by climate change. It recommends businesses (and Governments) to prepare to mitigate the impact of pandemics with the same urgency as they are for climate change.

- The George Institute, April 2014. Health leaders agree Australian health system unsustainable. Panel discussion at the Museum of Sydney to mark World Health Day.

- Ebell MH, Sokol R, Lee A et al. How good is the evidence to support primary care practice? Evidence Based Medicine 2017;22(3):88-92

- Bennett CC. Are we there yet? A journey of health reform in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 2013;199 (4):251-255. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10839

- Duckett S. Rationing care vs increasing taxes – the health system sustainability myth. In The Conversation, April 2014.

- World Economic Forum in collaboration with Harvard Global Health Institute. Outbreak Readiness and Business Impact. Protecting Lives and Livelihoods across the Global Economy. January 2019, Geneva.

- Pencheon M. Developing a sustainable health care system: the United Kingdom experience. Medical Journal of Australia 2018; 208(7). doi: 10.5694/mja17.01134

- Littlejohns P et al. Creating sustainable health care systems. Journal of Health Organization and Management 2019;34(1):18-34. doi:10.1108/JHOM-02-2018-0065