A universal dental benefits scheme?

Dental health is an important component of personal well-being. Poor dental hygiene, apart from making unpleasant company, has been reported to be linked to higher rates of systemic disease. In an almost 40-year prospective cohort study of Swedish adults, Wilson and colleagues (2018) concluded that poor oral health is associated with a slightly increased risk of myocardial infarction. However, they caution that the results may partly be explained by residual confounding, in particular to tobacco smoking.

Closer to home, the Australian Dental Association’s Oral Health Tracker (February 2018) makes for sobering reading with 15.5% of adults reported as having inadequate dentition (< 21 teeth); 25.5% with untreated tooth decay and only 51% brushing twice daily with fluoridated toothpaste. This last figure is 68.5% in children aged 5-14 years but even so, 23.5% of this age group have already experienced decay in their permanent teeth.

The most recent AIHW report on oral and dental care in Australia notes that total expenditure on dental services (except those in hospitals) was $8.7 billion in 2012–13. This was an increase of approximately 46% (adjusted for inflation) over the decade from 2002-03. Assuming a similar growth rate, this figure may be, conservatively, around $11 billion in 2019-20.

Who pays for dental services?

In 2013, the largest source of funds for overall dental expenditure was individuals, paying directly out of pocket for 58% of total dental costs.

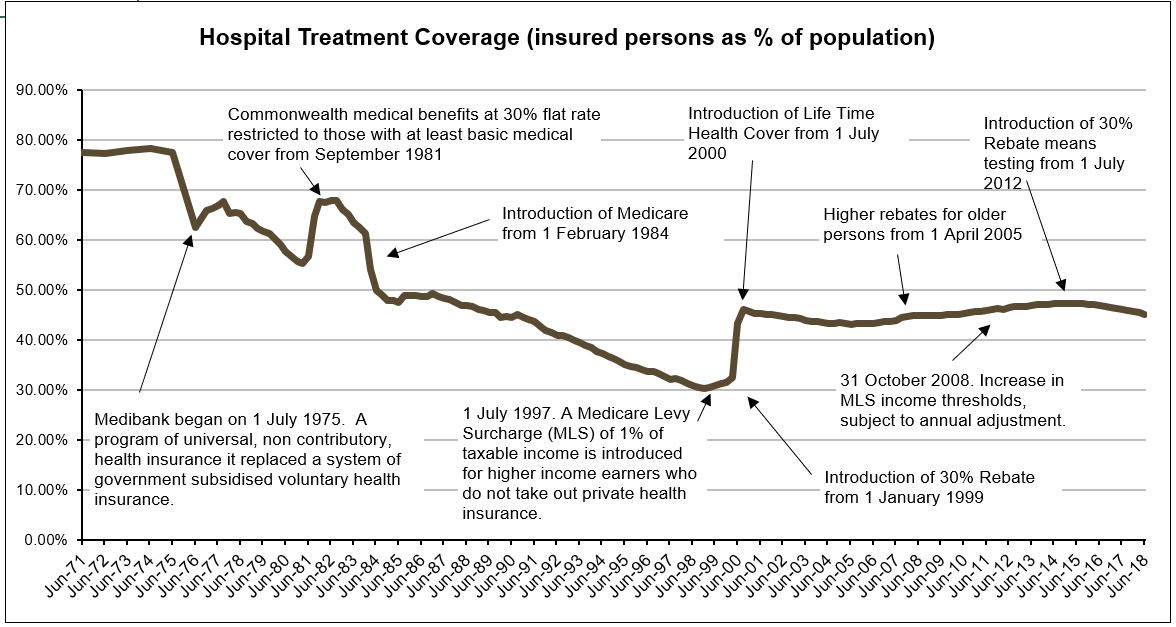

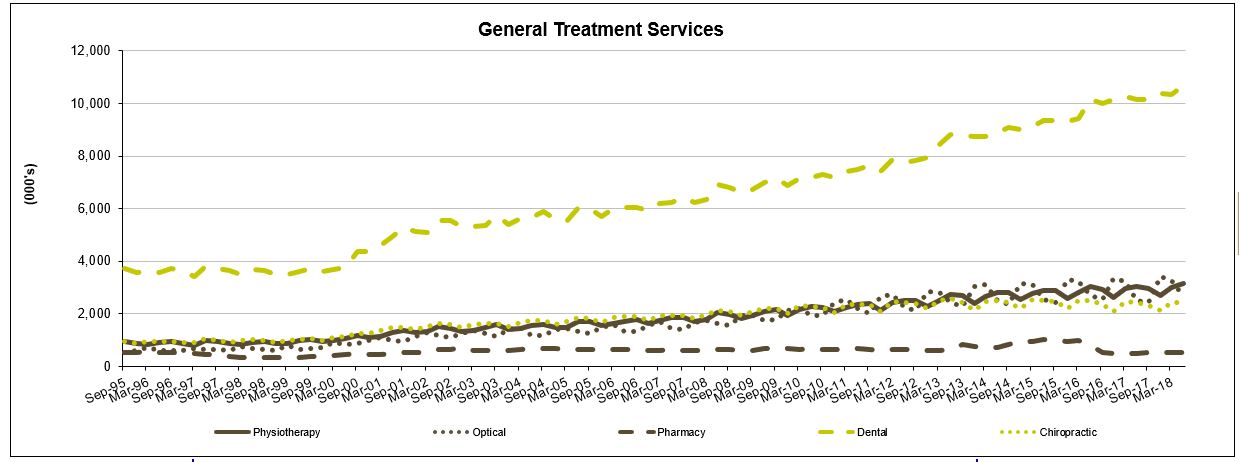

Of the 55% of Australians with dental coverage through their private health insurance, less than 10% of services were fully covered. The graph shows benefits paid for various extras services by private health insurers on a quarterly basis (APRA PHI Statistics). Dental services are clearly a pressure point and patient co-payments must be rising at a similar trajectory.

The Commonwealth Government can be said to contribute their part via the Private Health Insurance rebate (estimated to reach $6.5 billion by 2019-20). Additionally, a National Partnership Agreement on Dental services for Adults will provide approximately $316 million dollars to the States/Territories under the medical services sub-function for the same period. This infers that the States/Territories currently fund the bulk of public dental services.

A Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS) was introduced by the Federal Government in 2014 for children aged between 2-17 years whose family receives Family Tax Benefit Part A or a relevant Australian Government payment. Interestingly, in the 2018-19 Budget, expenses for dental services are forecast to decrease by 7.0 per cent in real terms over the period 2018-19 to 2021-22, reflecting lower growth in utilisation of the CDBS. Potentially, this is a result of ongoing changes to the scheme, up to version 7.0 as at 1 January 2018.

The Australian healthcare system is acknowledged for its universality, structured around the 3 pillars of public hospitals, Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). A fourth, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is being established. By 2019-20, these will represent 4 of the top 8 program spends for the Commonwealth Government, budgeted at $22.3, $25.5, $11.7 and $20.7 billion, respectively.

In such an environment, the fact that 30% of Australians currently go without regular dental care due to cost, unavailability of services and other barriers, seems like a blind spot. If dental health is a general indicator of personal health care practices, establishing good routines early in life may contribute to better overall population health. Isn’t that worth paying for?

The Final Report of the National Advisory Council on Dental Health (2012), established by the then Minister for Health and Ageing, the Hon Nicola Roxon MP and Senator Richard Di Natale, to answer this exact question, definitely thinks so. Dental policy options to achieve universal access are detailed and waiting…

Source: Cartoon, Donkey, from the Shrek movies.