The fate of ‘fee for service’ GP visits

‘Without structural change to the way in which health care is delivered and financed, the Australian health care system will continue to struggle to meet contemporary needs and expectations of its citizens.‘

Mitchell Institute Policy Issues Paper ‘Australian Health Services: Too complex to navigate’ February 2019

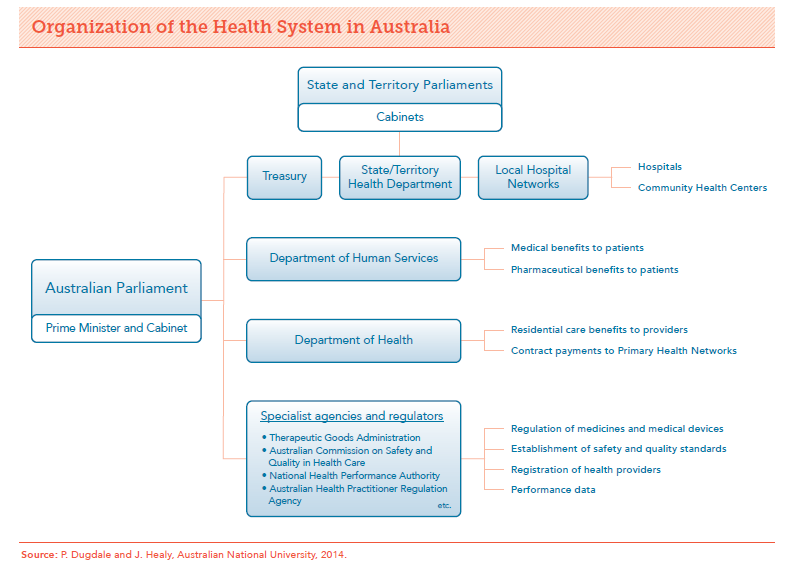

SIMPLIFICATION REQUIRED

An analysis of previous reviews of Australia’s health service was undertaken by the Mitchell Institute early this year. The authors report successive reviews concluded that existing funding arrangements impede the delivery of clinically effective and efficient health care, in particular for chronic diseases.

Consequently, the report, as those that have come before, recommends restructuring of current health financing arrangements to move the focus, and incentives, from high cost reactive healthcare towards investment in prevention services to reduce disease, as well as management of chronic health conditions.

A publicly funded universal insurance system in concert with private health insurance should be retained. However, the basis for remuneration of providers must ‘encourage sustained prevention, early detection and management of chronic disease and coordination of services to reduce duplication and more effective use of information’.

HEALTH CARE HOMES (HCH) TRIAL

It was on the basis of one such report (Dec 2015) that the Primary Health Care Advisory Group# recommended implementation of a Health Care Home model of care. The intent being provision of a ‘home-base’ (GP practice) for patients with complex and chronic conditions, where the care needed would be coordinated on an ongoing basis.

Stage 1 of the HCH program was to be trialled in 200 GP practices and enrol up to 65,000 patients (later modified to a cap of 12,000) by 30 June 2019. However, at this time only approximately 99 of the 175 registered practices were active with a total of 2,075 enrolled patients. The implementation of the pilot has been roundly criticised, with even the Royal Australian College of GPs withdrawing their support for the scheme (see August 2018 Medical Republic article).

In December 2018, the Government extended the HCH trial for an additional eighteen months to 30 June 2021. At the same time, it was announced that Health Policy Analysis (HPA), an independent organisation had been contracted by the Department of Health to undertake an evaluation of the implementation of Stage 1 in collaboration with experts from the University of NSW and the University of Technology.

In response to an enquiry, the Department of Health confirmed that this evaluation ‘is progressing well, with the second round of data collection and analysis under way‘. They also noted that ‘the evaluation has been extended to 2021, in line with the extension of the program. HPA will now deliver the final evaluation report to government late 2021. It will be a decision for government on whether to release the findings of the evaluation to a wider audience.’

IS LEGISLATION NECESSARY?

In 2012, the US State of Massachusetts enacted a law to control health care spending. This was in response to increases such that by 2010, costs of Medicaid and private health insurance for state employees accounted for almost 40% of the state’s annual budget. Key elements of the law include:

- limiting the growth of health care spending to growth in Massachusetts’ economy as measured by the gross state product (GSP);

- shifting from fee-for-service care to global payment models;

- supporting the formation of Accountable Care Organisations and patient-centred medical homes to improve quality and control costs; and

- promoting greater transparency through expanded public reporting of health care providers’ quality and cost data.

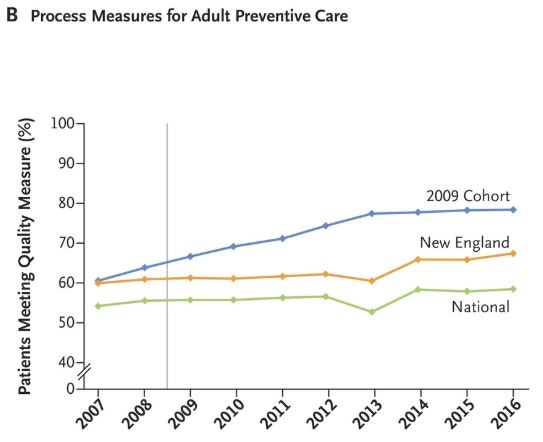

Eight-year results were reported in the NEJM in July (4), and demonstrate that global budgets and financial incentives for improving quality and controlling costs work. On a range of measures those patients treated under terms of the new law (labelled as 2009 Cohort) received better quality care compared to patients in surrounding States (in New England region), and the rest of the US (National). The graph shows the proportion of patients meeting quality standards for preventative care over time between these three groups. The grey vertical line is the introduction of the new law. Overall on the range of measures followed, patients experienced better health outcomes for less cost which must catch the attention of Ministers of Health!

# The Healthier Medicare initiative of the Abbott Government included establishment, by the then Health Minister Susan Ley, of the Primary Health Care Advisory Group to investigate options for the reform of primary health care to support patients with chronic and complex illness, including mental health conditions.

References

1. Hayes P, Lynch A & Stiffe J. Moving into the ‘patient-centred medical home’: reforming Australian general practice. Journal of Education for Primary Care 2016;27(5):413-15.

2. Song Z and Landon BE. Controlling Health Care Spending — The Massachusetts Experiment. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1560-1561.

3. Ayanian JZ and Van der Wees PJ. Tackling Rising Health Care Costs in Massachusetts. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:790-793.

4. Song Z, Ji Y, Safran DG and Chernew ME. Health Care Spending, Utilization, and Quality 8 Years into Global Payment. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:252-263.

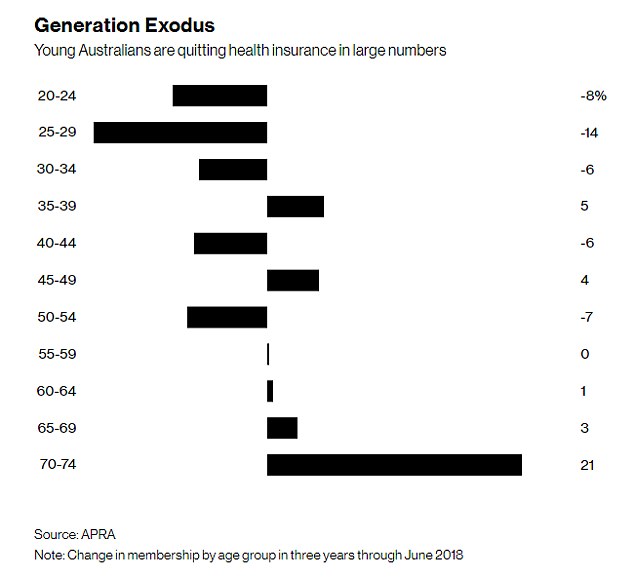

Unfortunately, individual patient needs do not really feature in the discussions. Analyses of which type of patients, procedures, and waiting times have contributed to the increase, and reporting of coercive techniques being used on patients to elect PHI, all point back to assumed financial benefit as the driver.

Unfortunately, individual patient needs do not really feature in the discussions. Analyses of which type of patients, procedures, and waiting times have contributed to the increase, and reporting of coercive techniques being used on patients to elect PHI, all point back to assumed financial benefit as the driver.