Globalisation and the pricing of biopharmaceuticals

As the Sponsor of a new medicine seeking listing on the national Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), pricing used to be relatively straightforward once a positive Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) recommendation had been received.

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Pricing Authority (PBPA), defunct as of 1 April 2014, would determine the price based on: (1) PBAC advice accompanying the recommendation and, (2) the Sponsor’s pricing submission. Calculation methods were explained in the PBPA Manual (last edition 2009) and, sometimes further discussion with the Pricing Section of the Department of Health (DoH) was required to finalise, for example, exact amount of cost offsets etc. From a company perspective, as long as you stayed above the specified ‘global floor’, the local price was a matter for the local affiliate.

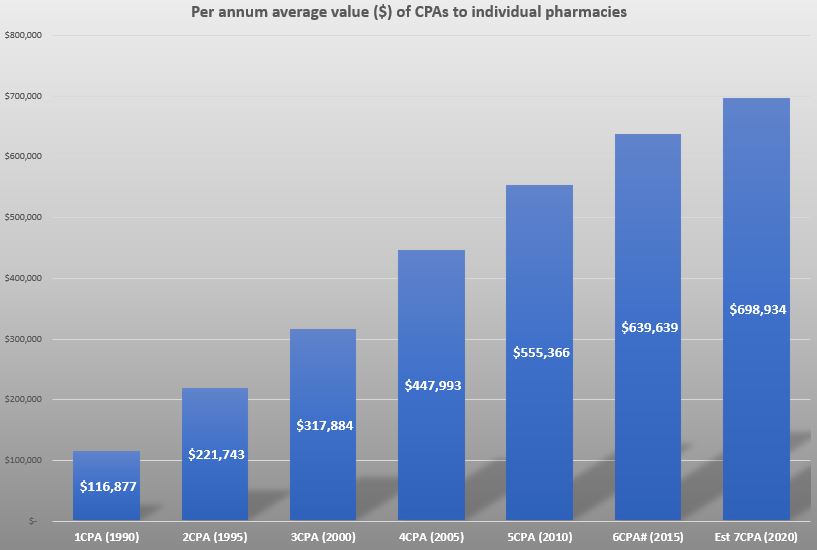

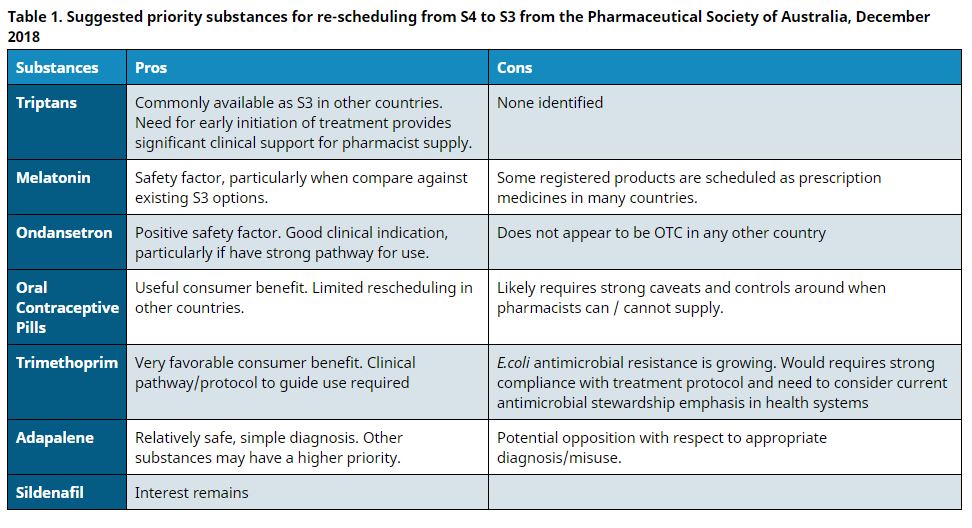

Prior to August 2007 reforms, when the PBS was split into two formularies (F1, F2) based on the availability of a generic brand following lost of exclusivity, the ‘reference pricing method’, was most commonly used. This is where drugs are priced based on their relative safety and efficacy, as determined by the PBAC and documented in Therapeutic Relativity Sheets. Where drugs are considered to be of similar efficacy and safety, the lowest priced brand or drug sets the benchmark price (‘cost-minimised’).

The ‘cost plus method’, where a gross margin of 30% is considered reasonable based on costs declared by the Sponsor in the PB11b form, became applicable to a larger range of drugs (F2, multiple brands) after the reforms, with reference pricing only applying to F1 (single brand, on patent) drugs.

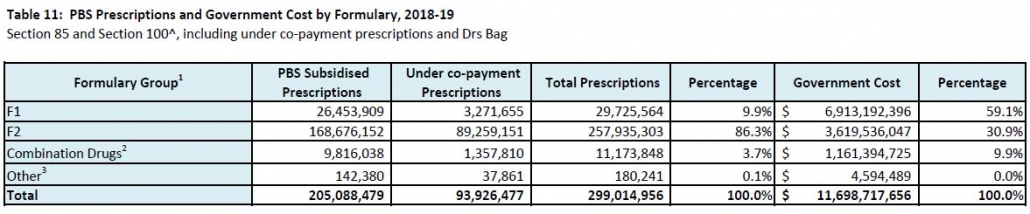

A Price Disclosure policy was introduced for F2 medicines. This was necessary for the Government to realise the savings when generic brands cost-minimised to originator brand prices. Generic companies were using the excess margin above cost, due to lower development investment, to incentivise prescribers and pharmacists. Various iterations to price disclosure processes have been extremely effective in finding the lowest viable price. This policy is almost wholly responsible for over 30% of PBS services currently being below the general patient co-payment ($40) and in no need of Government subsidy.

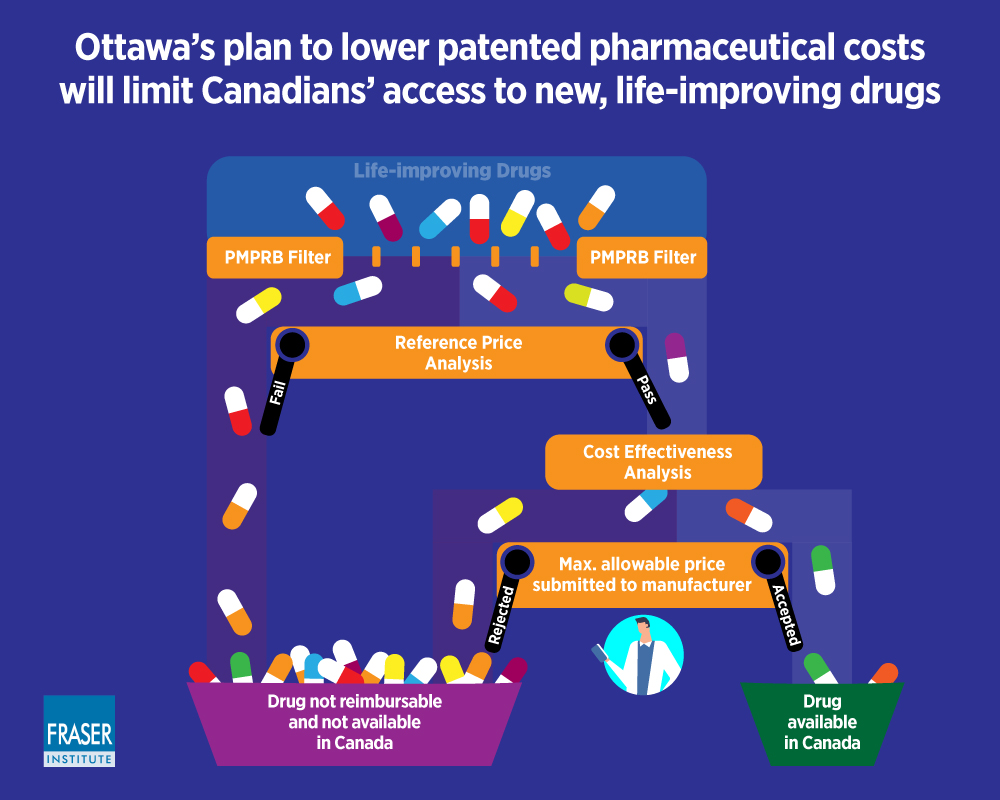

Continuing adjustments to policies and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) evaluation guidelines maintained Government pressure on prices and risk mitigation. This resulted in the need for Special Pricing Arrangements (SPAs) and Risk Share Agreements (RSAs), respectively. Rebates of 100 % are now the norm. When ‘effective’ (i.e. real) prices being paid for new medicines are lower than the global floor these must be confidential otherwise long delays to PBS listing are likely. This is because of the increasing number of countries who base their local drug prices on those paid by a basket of countries (international reference pricing). This approach is proposed in the USA as part of the Pelosi bill.

Where a comparator is listed under a SPA, preparing an economic evaluation has become a guessing game as to the effective price. Needing to use the published list price disadvantages a new medicine in the evaluation process.

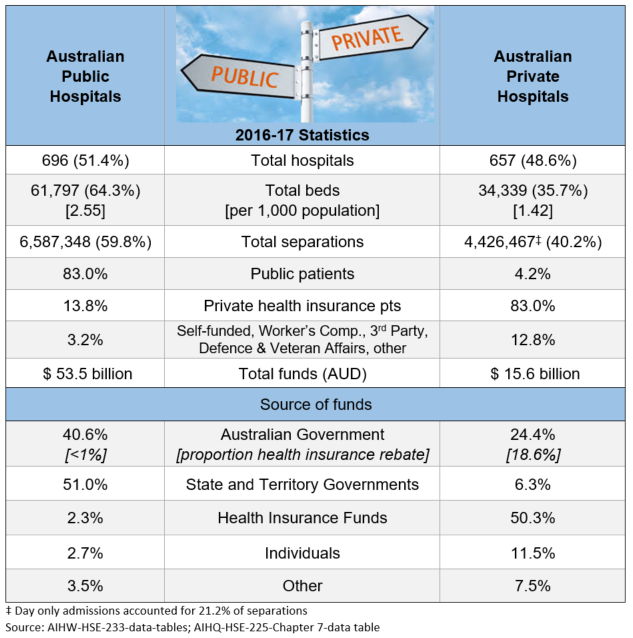

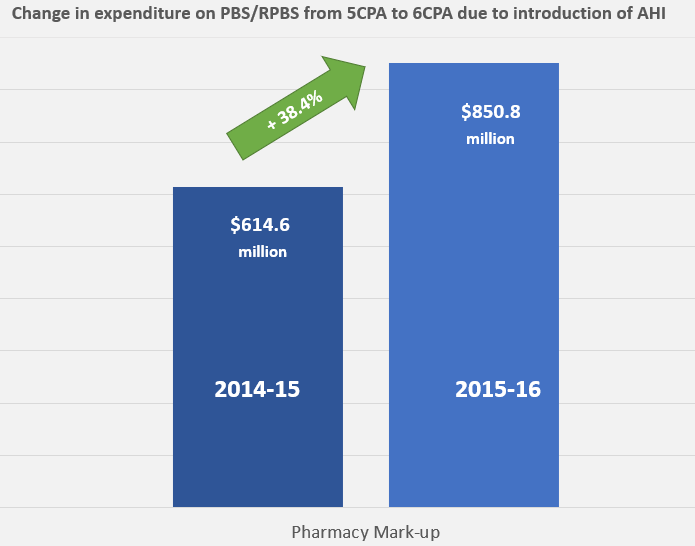

Things became more complicated when the PBS Access and Sustainability Package, introduced in mid-2015, included a 5% price cut to all F1 brands listed for five or more years. As the Table shows, F2 is a smaller source of potential savings for the Government. Anniversary cuts were extended to include 10 and 15 year listing marks as part of the 2017 Commonwealth-Medicines Australia Strategic Agreement.

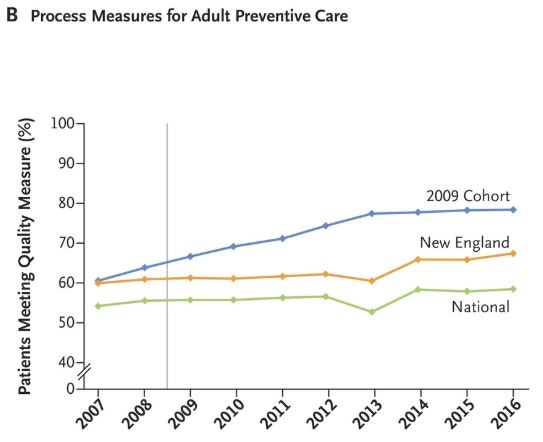

Affiliate pricing of a new medicine is increasingly centralised by companies as Government payers push to use taxpayers’ money wisely. In both situations, prices expected, based on perceived and relative value, may be very different to those modelled on the available clinical evidence.

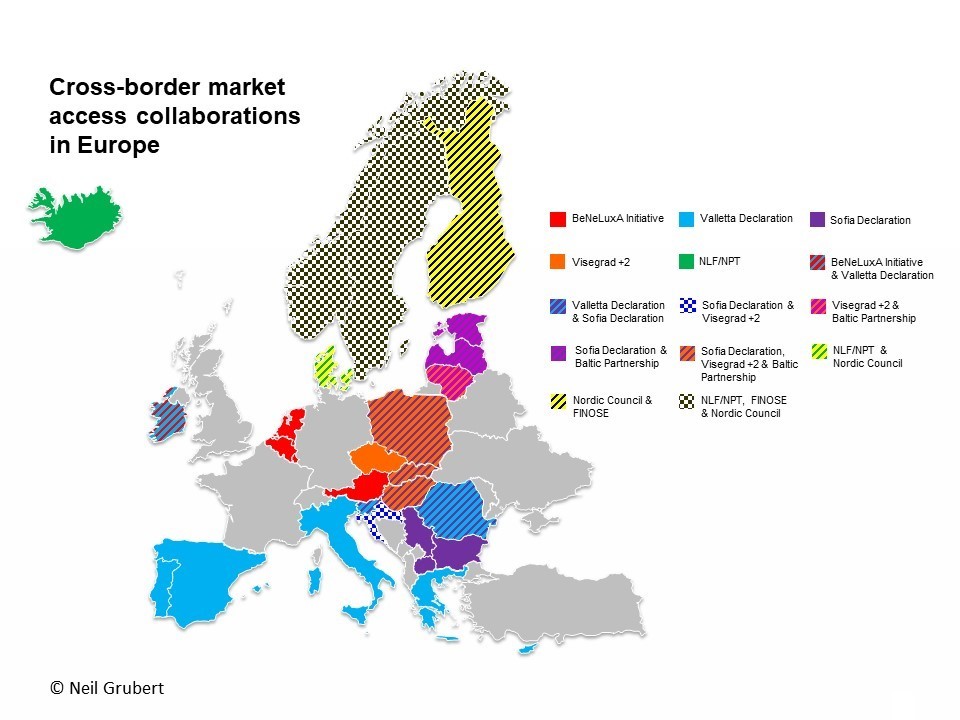

Collaboration between payers and pressure for reform (2), including transparency of real prices, may result in pricing becoming very simple if companies choose to set only one global price.

(1) Impact of introduction of value-based pricing in Germany (2) See articles by Neil Gubert on cross-border collaboration and the Commonwealth Fund on drug pricing reform.

Photo source: BIG Maze, National Building Museum, Washington DC, 2014

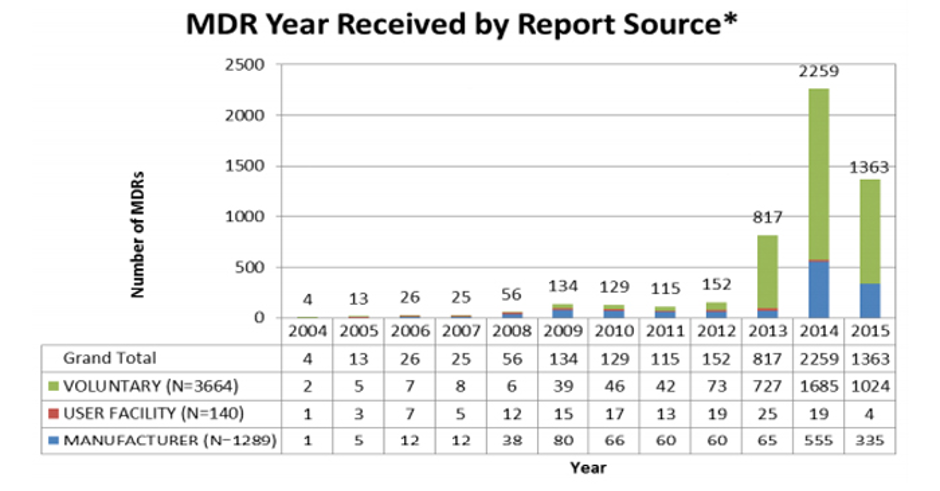

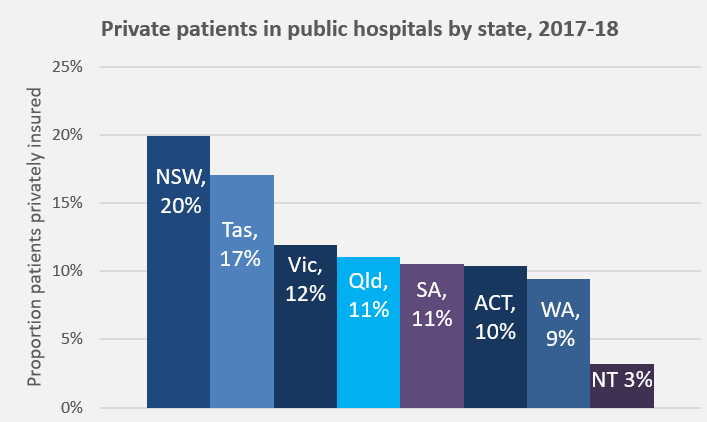

Unfortunately, individual patient needs do not really feature in the discussions. Analyses of which type of patients, procedures, and waiting times have contributed to the increase, and reporting of coercive techniques being used on patients to elect PHI, all point back to assumed financial benefit as the driver.

Unfortunately, individual patient needs do not really feature in the discussions. Analyses of which type of patients, procedures, and waiting times have contributed to the increase, and reporting of coercive techniques being used on patients to elect PHI, all point back to assumed financial benefit as the driver.